Inside The Race To Become The Chipotle Of Pizza

Why is America’s favorite and most ubiquitous food so hard to get right on a national scale? Several entrepreneurs are at the forefront of this booming fast-casual trend, but none more so than a man whose previous claim to fame was as the brother of America’s top tennis star.

Carl Chang smiles widely as he approaches me in the sprawling parking lot of the Irvine Spectrum, a giant outdoor shopping complex in Southern California. We head toward the busy restaurant he opened a few yards down, which, depending on whom you believe, may very well represent the future of pizza in the US.

“We want to celebrate creativity,” says Chang, CEO of Pieology, a budding chain based in Rancho Santa Margarita that specializes in casually upscale build-your-own pizzas. He leads me to a long counter where a sign suggests, “Discover the Possibilities.” Here, customers choose from three kinds of crusts, seven sauces, six cheese options, seven meats, and sixteen veggie toppings, which can be finished with an option of five drizzles, like pesto or “fiery buffalo sauce,” at the end. This adds up to “78 billion flavor combinations,” the menu points out — more than even the most committed pizza lover could tackle in a lifetime, and enough to lure plenty of regulars back to Pieology.

Of all the ingredients behind the counter, it’s the crust that draws the greatest zeal from Chang, a New Jersey native and devotee of the New York–style slice. “Our crust is a thin crust,” he explained — an obvious gap in California’s pizza scene outside of high-end restaurants. “A lot of the fast-food pizzas, their objective is to fill the stomach.” So generally, their crusts are heavier. Not so at Pieology, which considers its crust to be lighter and more refined.

Carl Chang Rebecca Aranda for BuzzFeed News

Behind the counter, a worker flattens a smooth globe of dough with a mechanical press into a slim 11.5-inch disc every time a personal pizza is ordered. Other ingredients, like spinach and fresh basil, are displayed in metal bins along the counter — lending some very 21st-century “freshness cues,” as Chang calls them — where customers select their toppings.

Each personal pizza, no matter how much you load on it, is $8.45. It’s more than you might spend on lunch at another pizza joint, but Chang asks, “How do you make a $5 medium pizza and still make a profit?” His mission is to lure the US’s delivery-addicted pizza eaters back into the pizzeria by way of a quality product made before their eyes at lightning speed — while still being affordable as an everyday lunch. He’s not a restaurateur by training, but he is consumed by a powerful nostalgia for good pizza, and this is an area he feels that America’s pizza giants have overlooked.

It’s all part of a wave of nouveau fast-food, thin-crust pizza chains that emerged on the West Coast after the recession and are now booming: In 2015, Pieology was named the country’s fastest-growing restaurant chain by food consultancy Technomic; this year two major Pieology competitors — Seattle-based Mod and Pasadena-based Blaze — claimed the top spots.

A pizza from Blaze Pizza (left), and Mod Pizza. Oriana Koren for BuzzFeed News

Pizza, like other fast food, proliferated in the US because it was cheap and convenient. Above all else, most Americans expect pizza to cost very little, which can be a recipe for all sorts of culinary shenanigans. While it was beloved for decades — even in the highly industrialized form most of us know today — the big chains lost their way somewhere down the line, in pursuit, perhaps, of efficiency and profit. But what other choice did a pizza enthusiast have?

Chang’s mission is to lure America’s delivery-addicted pizza eaters back into the pizzeria by way of a gourmet product made before their eyes at lightning speed.

At some point, enough people decided they were no longer content to just passively gorge on whatever pizza they were offered. In 2009, responding to persistent customer complaints like “Domino’s pizza crust to me is like cardboard” and “the sauce tastes like ketchup,” Domino’s launched a new pizza recipe. In 2014, Pizza Hut revamped its menu to focus on bold flavors like honey Sriracha crusts and balsamic drizzles, after two years of declining sales. This year, Papa John’s ditched artificial flavors and colors and launched an exhaustive list of other banned ingredients: no partially hydrogenated oils, no MSG, no fillers in meat toppings, no BHA, no BHT, no cellulose, and no antibiotics in its chicken toppings and poppers.

The recent explosion of so-called fast-casual chains like Chipotle and Shake Shack — which lie a notch above fast food while avoiding table service and tipping — got many to expect fresh, high-quality, non-GMO, grass-fed, and otherwise ambitious-sounding ingredients, even when they were grabbing a quick bite. It was only a matter of time before customers demanded the same of their pizza. What’s happening in pizza now is all very reminiscent of the chains that have boomed in the last decade by selling tuned-up versions of old-school junk food.

Each of the three new-school pizza chains have roughly 100 locations, with commitments from franchisees to build hundreds more. There are well over 30 fast-casual pizza concepts — some of which have been around for much longer than these three — testing the market across the country. But in the end, says Technomic’s president, Darren Tristano, “there’s room for two to three major-growth national chains.”

Chang hopes Pieology will hit 700 outlets within five years, riding on an ambitious goal: to hit the narrow sweet spot between the speed and convenience of the top fast-food joints while also offering food worthy of a gourmet pizzeria. Five thousand Pieology employees have come to count on him to succeed. In Chang’s way are plenty of competitors — both startups and giants like Pizza Hut that are evolving in the same manner — who might do it better, and who stand to completely displace Chang and his oven-fired army from the second coming of pizza, reducing his ambition and his vision to little more than another half-baked pie in the sky.

A pizza from Pieology. Rebecca Aranda for BuzzFeed News

Just past noon on a Monday at Pieology, Chang observes the lunch crowd that has already started claiming seats indoors and out — 65% of the chain’s customers dine in, and the other third take their pies to go (at Pizza Hut, the majority of orders are for take-out or delivery). Chang is wearing a T-shirt and vest. The restaurant crew greet him. He speaks slowly and deliberately. If you were to create a cartoon character based just on his voice, which has a slight nasal tinge, he would wear glasses.

Inside, customers queue up along a wall decorated with dozens of inspirational messages, like “A wise man will make more opportunities than he finds” (Sir Francis Bacon) and “You’re never a loser until you quit trying” (Mike Ditka). It’s part of Pieology’s new design, meant to look “less like Chipotle” than the previous decor did, Chang says. The store is outfitted with wood finishings and black tables and chairs. Exposed ceilings and vents lend a subtle industrial vibe.

What’s happening in pizza now is all very reminiscent of the chains that have boomed in the last decade by selling tuned-up versions of old-school junk food.

Nothing about Chang suggests he should be at the vanguard of a pizza revolution. The 47-year-old father of four still has a full-time job as CEO of a real estate business; the restaurant was meant to be a hobby. He never went to culinary school, and has never worked at a pizza joint. If the name Carl Chang rings familiar at all, it’s probably as the older brother and coach of Michael Chang, who in 1989 became the the youngest male player to win a Grand Slam singles title, taking the French Open when he was just 17. Michael was called “a prodigy” and multimillion-dollar endorsement deals came his way, all before he was old enough to buy a lottery ticket.

“I’ve always been the guy that has the famous brother,” Chang says. “I always joke about changing my name on my birth certificate to Michael Chang’s Older Brother.” But in just five years, Michael Chang’s Older Brother has begun to build a name for himself. In 2015, Pieology rang up $80 million in sales across all its restaurants, and it expects sales to hit $225 million in 2016. Blaze’s sales surpassed the $100 million mark last year, while Mod took in $65 million.

“Everyone feels like this is the next big category,” says Rick Wetzel, founder of Wetzel’s Pretzels, who launched Blaze Pizza in 2012 with his wife, Elise. Data from Technomic shows that while sales at regular fast-food pizza chains grew by 5.3% in 2015, sales at higher-end fast-casual pizza chains grew by 36.7%.

They’re designed to be attractive for walk-in customers and the lunch crowd, and they aim to churn out a pizza as quickly as fast food’s speediest options, having adopted Chipotle’s and Subway’s build-your-own, assembly-line model.

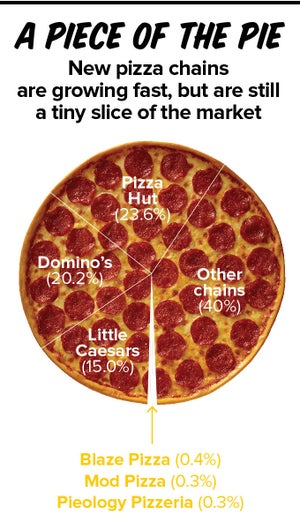

Source: Based on Technomic’s 2015 data on the 500 largest restaurant chains in the US. Does not include small and independent pizzerias.

Chipotle has called its speed an “enormously huge competitive advantage for us and a huge part of customer service,” and its would-be pizza competitors have taken that to heart. In a ritual familiar to any Chipotle regular, customers walk down a line and tell a crew member on the other side of the counter what sauces and toppings to put on their personal pizzas. Eventually they pay at the register, as their pies are baked in less than three minutes thanks to some modern twists on very Old World Neapolitan cooking. It takes some work. Each pizza at Blaze gets thrown into a fiery oven and is monitored by an employee who skillfully twirls the pie on a board so that it cooks quickly and evenly.

Chang says a Pieology restaurant can handle 150 orders per hour during the two-and-a-half-hour lunch rush; a single Blaze restaurant can make about 175 pizzas per hour at lunch — that’s nearly one every 20 seconds. Creating a personal pizza begins with a selection from three crusts: regular “house-made,” whole wheat, or gluten-free. Then a choice of sauces: red, three-cheese Alfredo, herb butter, olive oil, buffalo, pesto, or barbecue. A couple of steps down are the cheeses: mozzarella, ricotta, Parmesan, feta, Gorgonzola, and vegan mozzarella.

“I love cheese,” Chang said. He paused and whispered: “I looooooove cheese.” Pieology’s mozzarella, in fact, is a proprietary one that Chang developed with his supplier (who he said was a big enough fan of tennis and his brother Michael to give them good pricing) to get the precise blend of buttery but not-too-salty cheesiness he pined for. It gets shredded in-house: “It has to be a certain length and a certain width.” Chang also developed Pieology’s sweet, herby, ever-so-subtly spicy red-sauce recipe over a year and a half. “Tomatoes are so different. Oh my goodness. Some tomatoes are sweeter, some are richer, some have no taste whatsoever. Some you can tell weren’t vine-ripened,” he says. “You just can taste it.”

Nodding to a trend taken mainstream by Chipotle and other fast-casual restaurants, Pieology and its peers all pay particular attention to the provenance of their ingredients. Customers will find such hyper-self-aware ingredients as “California, non-GMO, 50-year-old seed-stock roasted garlic” at Blaze, and flours that are “never bleached and never bromated and have no unnecessary chemicals” in Mod’s dough.

“It is time to make it work for the lifestyles of here and now,” says Ally Svenson, who in 2008 co-founded Mod with her husband, Scott, formerly the president of Starbucks in the UK. For Svenson, pizza “has been around forever and will be around forever, but what works for us now is different from what worked for us before.”

A prep station at Mod Pizza. Oriana Koren for BuzzFeed News

There already is a literal “Chipotle of pizza,” even if it has been overshadowed by faster-growing franchises. In 2013, Chipotle itself invested in a pizza chain started in Boulder in 2011 called Pizzeria Locale. It now runs four restaurants and will soon grow to seven, all company-owned, with no plans to rev up expansion by franchising.

“Chipotle paved the way for the idea that just because it’s fast, it doesn’t have to be a typical fast-food experience,” says Lachlan Mackinnon-Patterson, a co-founder of Pizzeria Locale. In the same tenor as Chipotle’s executives, the chef explains that his vision is to “change people’s pizza habits at a broad scale and change how people thought about fast-food pizza.”

To win the office lunch crowd, a chain needs to make a plausible case that it’s selling a food that is okay to consume on a semi-regular basis — and that’s one major roadblock for the new pizza chains. The National Institutes of Health specifically names pizza among foods teens should avoid, along with candy, soda, and fast food, which “have lots of added sugar, solid fats, and sodium,” the site explains. “A healthy eating plan is low in these items.”

“We’re still at home plate with that,” Mackinnon-Patterson acknowledges. “I don’t even know if we’ve left the plate, really. We’re just starting to walk to first base.”

A worker at Mod Pizza prepares asparagus. Oriana Koren for BuzzFeed News

Chang agrees that it’s still early days, mainly because he sees such large long-term opportunity. He foresees expanding Pieology not only in the US but overseas, too, and it’s keeping him very, very busy.

As Chang prepares to order at the Irvine restaurant, he runs into Pieology’s franchisee for the Southeast US, who has committed to opening 48 locations. Moments later, as he tries to settle into a table outside for lunch, a customer introduces himself — he’s visiting from Iran, he says, and is interested in potential business opportunities. Chang gives him his cell phone number.

“There’s certainly a lot of demand for it,” Chang says of international expansion, as he finally digs into his plain cheese pie. “We’re going to start preparing for it for sure.” This includes Asia, where he hopes to take advantage of the relationships he had built from Michael’s tennis career.

This assumes a lot of confidence in demand for fast-casual pizza, yet what the future of pizza should look like can be a deeply touchy subject. Few foods inspire fanaticism like pizza — thin-crust versus deep-dish, red or white, traditional or experimental, fork and knife versus handheld. There are stark regional differences too, and neither Blaze, Pieology, nor Mod have made their way to the US pizza capital of New York City yet.

On any given day, 13% of Americans eat a slice of pizza. But even a number like that can underestimate the strength of our national feelings on the topic. “Pizza” is the number one food search on Google in the US, and is searched for six times as often as “Kim Kardashian.” The pizza is the most popular emoji on payment app Venmo. Beyoncé once called pizza her “favorite indulgence.” One person felt passionately enough about the power of pizza to pay $2.6 million for the domain pizza.com in 2008.

“Pizza’s a personal food,” Chang chuckles. “It’s been around forever.”

Pizza enthusiast Scott Wiener finds the food so magnetic that he has devoted his life to it: Wiener leads pizza tours in New York City, writes a column for the hyper-specialized trade publication Pizza Today, and does consulting work for pizzerias. When he travels, Wiener even brings testing kits with him to examine the water quality in various cities to better understand the age-old question of how much a region’s water affects the character of its pizza. “I am,” he concedes, “100% pizza.”

And as far as Wiener sees it, fast-casual pizza may be an upgrade from what most Americans now have access to, but his experience with this new genre has mostly been disappointing so far. “My problem with it is that it puts all of its emphasis on speed,” he says. As much as any of the chefs at these young chains have agonized over their recipes, making a pizza every 20 seconds means the consumer experience is “not so much about food — it’s more about convenience,” in Wiener’s opinion. And where’s the romance in that?

Even more troubling for chains like Pieology are avid consumers like Mikey Rodriguez, who runs the pizza-centric Instagram account @obsauced and loves pizza enough to consume it “for breakfast, lunch, and dinner,” yet considers the fast-casual trend to be one of “the worst things to happen to pizza” in recent history. “You have all these different kinds of pizza that have their own qualities, including bake time,” he says. Fast-casual pizza is limited in nature, as it can only include styles that cook quickly. “You can’t rush a craft.”

The oven at Mod Pizza. Rebecca Aranda for BuzzFeed News

Ask Carl Chang about pizza, and it quickly becomes clear that the real estate executive (he’s also CEO of Redwood Real Estate Partners) is not short of opinions, which are informed as much by his Chinese heritage as his travels to Italy. “I look in the mirror and raise an eyebrow at myself. Really, Chinese dude?” he says. “No one has approached me on it, but I look at myself and say, Really?!” Of course, no one ever said Asians can’t make good pizza: In 2010, a Japanese chef named Akinari Makishima was named the world’s best maker of traditional Neapolitan pizza.

At Pieology, the legacy of Chang’s Chinese upbringing manifests in the crust, which he says should be “crisp, and yet not crackery, with that chew — like my mom always told me about noodles.”

“When you bite into a great Asian noodle, it can’t be soggy, or mushy,” Chang says. “It has to have that jin’er,” referring to the Chinese word for vigor or strength. Of course, pizza crust isn’t noodles. And how much “jin’er” this Italian dish is even capable of having is up for debate. But what Chang looks for, in pizza crust and in noodles alike, is “that snap, that texture.”

“I look in the mirror and raise an eyebrow at myself. Really, Chinese dude?”

The way Chang and a long line of pizza makers see it, the crust is the bulk of the battle to making a good pizza — he spent a year and a half meticulously experimenting to develop Pieology’s crust. Chang drew from his experience as a child back in Queens, hanging out behind pizzeria counters with his friends, as well as cooking noodles and pastries with his mother. In 2008, he became an investor in Mod. (Mod later sued him for stealing its ideas; they settled out of court. Both parties declined to comment on the lawsuit for this article.)

The problem Chang confronted in California, where he’s lived on and off since age 9, was that the pizza scene was dominated by big chains like Domino’s and Pizza Hut, offering little in the way of a New York–style pie. It’s one of the things he wants to change with Pieology. The chain’s crust is thin and chewy with a crisp exterior, dotted with crunchy bits of cornmeal on the bottom. Brushed with oil, it glistens in the light and is moist enough to bend gently as you lift a slice.

Despite the 78 billion–ingredient combinations purportedly possible at Pieology, Chang favors the absolute simplest one: a house-made crust brushed with olive oil, with mozzarella cheese, and topped last with dollops of red sauce. He calls it an “upside-down cheese” pizza. It’s a little inside-out, but a basic pie such as this, he said, is the best way to judge if it’s any good.

Rebecca Aranda for BuzzFeed News

“Obviously you can put a lot of toppings on pizza,” he says. “But I want to know how good the crust is. I want to know the quality of the cheese, how it melts, how it tastes. And the sauce, I want to know if it’s out of a can. You can taste the tin, and I’m just not a fan of that.” And anyhow, it’s the Italian way. “All the years I was traveling in Rome, I found, their pizza is pretty simple.”

Blaze Pizza’s chef Brad Kent — a graduate of the Culinary Institute of America who also holds a degree in food science — has his own strong opinions about the crust. Kent dedicated years to crafting a crust for his first LA pizza restaurant, Olio, which Zagat concluded was “unique and perfect.”

Pizza crusts should hold their shape as you lift a slice, Kent explains to me at Blaze’s Pasadena outlet, where he’s ordered a “Green Stripe” pie with pesto, chicken, and arugula. Using cornmeal to prevent the dough from sticking makes no more sense than “eating polenta with pizza,” so he prefers dusting it with flour. And the raw dough should not be brushed with oil, the way they do it at Pieology, as this makes it soggier. At Blaze, olive oil gets drizzled on only after the toppings have been added.

The maniacal focus on crusts makes sense if you think about what a pizza really is. It began in Italy as a kind of bakery item — something approximating focaccia more than the product we recognize as pizza today. There are few rules on what goes atop a pie these days, whether it’s barbecue sauce or ranch, “breakfast pizza” with eggs and sausage, or “dessert pizza” drizzled with chocolate. No matter the toppings, it’s pizza as long as it’s on a crust.

So the crust, by that logic, is fundamentally what makes a pizza a pizza. And it had better be good.

Dough prep at Blaze Pizza. Oriana Koren for BuzzFeed News

As American entrepreneurs try to claim the future of pizza, purists insist that it was perfected in Italy generations ago.

Chang himself sampled his share of Italian pizza during his brother Michael’s tennis tours. “Often I would order a pasta and Carl and I would share a pizza,” Michael recalls. “It would be thin-crust, pretty sizable, minimum toppings to keep the crust thin, and it would be cooked in a wood-fire stove so you could peek in and see the pizza cooking.”

Food historians trace pizza back to the 1700s — mainly as sustenance for the poor in the crowded city of Naples. “A small slice for breakfast cost as little as a penny while a twopenny slice would suffice for a child’s school lunch,” wrote Carol Helstosky, a history professor at the University of Denver, in Pizza: A Global History. Pizza makers would sell their products to street vendors, who would walk “with a box of pizzas and an oiled board under the arm, ready to cut a slice according to the customer’s appetite and budget, or perhaps setting up a table on the street corner where pizzas sat in the hot sun, being consumed by flies until a human customer came along.”

Two girls enjoying a pizza during circa 1955. Orlando / Getty Images

It generally wasn’t favored among the upper classes, but the legend goes that Queen Margherita visited Naples in 1889 and, tired of eating French food, asked pizza maker Raffaele Esposito to make a variety of pizzas, according to Helstosky. Esposito made three kinds, one with lard, caciocavallo cheese, and basil; a second with fish; and a third, “pizza alla mozzarella,” with tomato, mozzarella, and basil. Queen Margherita favored the third, henceforth known as “margherita” pizza. This was a magical moment for pizza. It was eaten by the poor, and by the queen, said Blaze’s Kent. Pizza broke out of class boundaries — it was for everyone.

It wasn’t until the mid–20th century, after Italians immigrated to the US and soldiers returned from Europe, that pizza caught on here. The food then spread both domestically and across the world with the help of American franchises like Pizza Hut (founded by Irish-American brothers in Wichita in 1958) and Domino’s (founded in 1960 in Ypsilanti, Michigan, by Irish-American brothers who bought a small pizza store called DomiNick’s). A helping hand in the globalization process came from technologies that popularized frozen grocery-store pizza.

Gradually, US pizzerias engineered the speed out of pizza — the fast-cooking thin crust had a slim margin for error, Wiener says. Many chains adopted conveyor-belt ovens for consistency, but this extended the cooking time and degraded the texture of that all-important crust, Chang says.

“It’s just a very different texture and eating experience than something off a rotating conveyor belt,” he says. “It’s like, would you rather have a flame-broiled burger or a microwave burger?” And because the pizza business evolved to center on delivery, the pies were engineered to stay warm in a box at the expense of taste.

The Hav-A-Pizza restaurant in New York City, circa 1955. John Spencer Fay / FPG / Getty Images

Thanks in part to pizza’s ability to evolve to satisfy the tastes of each culture it touched, US chains turned the food into one of the world’s most popular cuisines — whether it’s shrimp and pineapple pizza in China, or mayonnaise and potatoes in Japan. While purists may recoil in horror at such ideas, pizza has long been prone to transformation.

Many chains adopted conveyor-belt ovens for consistency, but this extended the cooking time and degraded the texture of that all-important crust.

Even in the oldest of old-school New York City pizza houses, many of the basic components of classic pies are a far cry from the cuisine’s Italian roots. Pepperoni, for example, is American-style salami. The first print reference to “pepperoni,” according to food historian John Mariani, dates back to only 1919, as Italian butcher shops proliferated in the US.

And while Hawaiian-style pizza — the kind topped with pineapple and ham that has on occasion been called a “Polynesian perversion” — may sound like an American creation, it in fact was created in Ontario, Canada, by a Greek immigrant who was experimenting with the sweet and sour flavors of Chinese food in his restaurant. Hawaiian pizza eventually traveled overseas, becoming massively popular in Australia.

Later came stuffed-crust pizza, popularized by Pizza Hut in the 1990s, then crusts stuffed with hamburgers and hot dogs overseas, and Papa John’s pies topped with Fritos and chili sauce in the US. Had innovation spun out of control? “That is the absolute antithesis of what we are looking to do here,” Blaze co-founder Elise Wetzel said of Fritos toppings.

Before such abominations were let loose on the world, an Italian nonprofit called Associazione Verace Pizza Napoletana, established in 1984, set out to preserve the tradition of Neapolitan pizza-making. It offered “VPN” certification to pizza makers who adhered to its standards for ingredients, equipment, and technique.

The original Pizza Hut building in 2004 on the campus of Wichita State University. Sanjay Acharya, Wikipedia

“We are against the cultural and commercial deformation of our pizza and against its industrialization; in fact, the ready-to-eat and frozen pizzas sold in supermarkets have nothing to do with the original ones,” the founder of the association once said. There are now nearly 90 US members in the AVPN — a respectable number, but hardly even a drop in the bucket compared with the more than 74,000 pizza joints spread across the country.

These authentic Neapolitan pies earned the respect and appreciation of the new fast-casual pizza entrepreneurs, and while their restaurants hint at going back to the basics, not one of them identified their goal as preserving Italy’s pizza heritage. Instead, they’re each trying to stake a place in pizza’s next chapter.

While Pieology’s Chang is doing his part to gentrify pizza now, like pizza’s earliest devotees he grew up in and out of poverty. During the first years of his life, he lived in a Hoboken housing project. After both of his parents lost their jobs years later, on the toughest evenings the family would share a single egg over rice. “You did what you had to do,” Chang says. “We were just a simple family having a tough time making ends meet, but we’d just eat around the community table, and share that bowl of rice with that one fried egg we could throw on top.”

When things were less dire, there was pizza — usually plain cheese. “If you had to get one large pie and feed so many people, you really couldn’t satisfy everyone. So you tend to fall on the common denominator,” he says. The idea at Pieology is that diners don’t ever have to compromise on a common denominator.

Pizzas from Mod Pizza. Oriana Koren for BuzzFeed News

The kind of pies favored by new-school chains like Blaze and Pieology fall somewhere between traditional Neapolitan pizza and the anarchy of the big American chains.

Today’s young consumers, Chang believes, “want to control how the pizza is made, the toppings, the quality, the execution. … And we threw a twist on that: Instead of being charged per topping, why not create a model where you have so much control over how you want to build your own pie, and the freedom to do so limitlessly all for one price? And we actually pulled it off.”

Despite all the hubbub about artisanal toppings and customization, it’s the Neapolitan-style cooking times that define the new-school pizza joints. It turns out that while most Americans have gotten used to waiting half an hour to have their pizza delivered or served to them by a waiter, pizza is an ideal product for a fast-food lunch: An authentic VPN-certified margherita pie can cook in one minute. The new-school pizza chains see this ability to turbo-bake as central to making quick grab-and-go pizzas available to the lunch-hour masses.

Whether or not one of these franchises manages to become the Chipotle of pizza, their formula seems to be working. The average franchised Pieology makes $1.3 million in sales per year. Blaze restaurants take in about $1.5 million each.

It’s far exceeded any expectations Chang may have had when he promised his wife, Diana, he would just open one location by Cal State Fullerton in 2011 while he continued to run the real estate company. Sitting in their dining room at home, Diana recalls how years ago she said, “This is your dream; let’s just do it. We’ll have fun.” Carl Chang laughs wildly. “She said, ‘Just one, right?’” Yet as competing chains like Blaze expanded in the LA area, he says, a deep instinct nurtured during his days in tennis was revived: “The competitiveness turned on.”

But even Michael Chang knows that competitiveness only goes so far. “We’ve seen quite a few tennis players open up restaurants,” he says. “It’s a tough business. We’ve seen a lot open and a lot of them close. If [Carl] had said, ‘Hey we want to open up 100 stores within five years,’ I’d probably be more hesitant. But he had the mentality of, ‘Hey, we just want to open one store first and see how it goes.’ I think that’s reasonable.”

Meanwhile, Pizza Hut’s US store count declined by 41 in 2015. Still, the biggest losers last year were independent pizza restaurants, which have been struggling against chains old and new.

Whether or not one of these franchises manages to become the Chipotle of pizza, their formula seems to be working.

Pizza Hut spokesman Doug Terfehr said that unlike the fast-casual competitors, which rely on walk-in traffic, Pizza Hut is a full-service restaurant and a delivery business, and “we feel that customers recognize that difference.” Yet even Pizza Hut announced in 2015 it will update 700 stores each year through 2022 to keep up with trends, and roll out new ovens that — like those at the new fast-casual chains — can cook pizza in three minutes.

Even if the new fast-casual chains are still a minuscule part of the of the $38 billion US pizza business, they have attracted plenty of attention from investors. Mod to date has raised more than $100 million, while in 2015, Blaze added LeBron James to its roster of investors (James decided not to renew his endorsement deal with McDonald’s). Earlier this year, the 1,900-store Chinese fast-food chain Panda Express announced that it had bought a minority stake in Pieology.

All that money being thrown around means tough competition, especially for these three chains, which all offer similar menus, prices, and experiences. After all, how many different ways are there to be the Chipotle of pizza? Pieology has fallen behind Mod and Blaze in terms of store count — and then there are the 30-plus other chains fighting for their share of pizza dollars.

The long-term challenge for the new fast-casual pizza chains will be facing off not only against the thousands of pizza outlets already opened by the established giants, but also the other fast-casual chains that have nothing to do with pizza at all. “We compete for the same market share as the burger brands, and Panera and such,” Chang says. “We tend to be great co-tenants, because we tend to be drivers for the same dayparts and similar consumers.”

Chang watches as customers nosh on their customized pies. He may be at the vanguard of a pizza revolution, but Pieology has reached a point where Chang needs more than the 37 people now working at headquarters to manage the next phase of expansion. The founder will eventually have to shift some of his executive powers to other people he trusts.

“I really don’t want to be the forefront of the brand,” he says. “I’d rather stay behind the scenes. I’d rather be the unknown face and let Pieology stand on its own. That’s always been my comfort zone. I grew up that way; I’ve always been behind the much more famous brother. I’m okay with that.”

Source:BuzzFeed